Problem Gambling Severity Index Uk

The Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI; Ferris & Wynne, 2001) is one of the most frequently used instruments to identify and quantify risk and problem gambling. The PGSI was developed specifically to measure problem gambling in the general rather than in a clinical population (Holtgraves, 2009).

Of the clients who completed treatment between April 2019 and March 2020, 90% showed improvement on the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) scale. Even better, of the individuals who qualified. The Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) 10 does offer a spectrum of harm categorisation; however, it was originally developed to measure general population problem gambling prevalence based on self-reported gambling behaviour rather than determinants of physiological or psychological harm, and may be too long to administer in a busy primary care practice. Some 12,161 adults were surveyed between 24 September and 13 October 2019, with researchers using the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) to decide if someone was a low, moderate or high risk gambler. It found that 13% of adults scored one or higher on the PSGI scale.

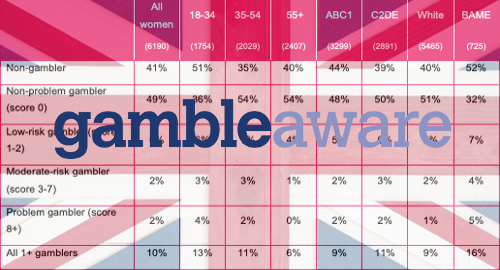

BAME background women at higher risk

Research completed for UK charity GambleAware by YouGov shows that over a third of female problem gamblers in the United Kingdom come from a black, Asian, or minority ethnic (BAME) background.

The survey from YouGov’s online panel of UK adults found that 35% of female gamblers who experienced high levels of harm – scoring 8+ on the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) – are from a BAME background, compared to 12% of the overall female population.

Male gamblers show a similar statistical profile. 29% of men with a PGSI score of 8+ originate from a BAME background versus 12% of men overall. In total, 10% of women scored one or higher on the PGSI index, lower than the proportion of UK men (17%) within the same score bracket.

Disproportionately affected by others’ gambling

BAME women are also more prone to experiencing harm as a result of someone else’s gambling. Of the 8% of women fitting into this “affected other” category, 16% hail from a BAME background. Researchers also revealed that females are more negatively influenced by the gambling of a close family member than men.

an important first step”

Marc Etches, CEO of GambleAware, said that in light of discovering how women experience gambling harms in different ways to men, the report represented “an important first step” toward understanding how women are impacted.

Highlighting that the research was commissioned to help treatment providers “address any barriers people may face” when accessing help and support for their gambling, Etches added in the press release that it was essential that services are flexible and meet the needs of individuals. Last year, one UK expert said curing a drug habit was easier than quitting gambling.

Stigma a hurdle to seeking treatment

One of the key factors in female gamblers not wanting treatment or support in cutting down gambling was the perceived stigma in seeking help, the report said. Nearly two in five women (39%) cited emotions such as embarrassment and fear of people finding out as barriers preventing them from seeking help.

Over a quarter (27%), however, said that having the option of self-referral and knowing easily accessible support was available over the telephone – either online or face to face – would be a motivating factor.

support to help reduce and prevent gambling harms among women”

Anna Hemmings, CEO of GamCare, said the report outlined the “opportunities available to service providers to help increase take-up of treatment and support to help reduce and prevent gambling harms among women.” As an independent UK charity, GamCare provides support and treatment for problem gamblers while helping to raise awareness about gambling harm and responsible gambling.

Hemmings reported that the treatment network she represents, in tandem with the National Gambling Treatment Service, was working with women to better understand the barriers they faced and to ensure they have access to services “regardless of their gender or background.”

As the government considered what to do about fixed-odds betting terminals last week, Malcolm George, chief executive of the Association of British Bookmakers was discussing whether they were really a problem.

'These machines were introduced 15 years ago. Since that time the levels of problem gambling in the UK have not risen,' he said.

The machines became widespread after changes to the taxation on gambling in October 2001. There are now more than 34,000 of them. They generated a gross gambling yield (GGY) of £1.8bn between October 2015 and September 2016 (GGY is the measure of all money staked minus the amount paid out).

To put that into context, it's about 13% of the GGY of the UK gambling industry as a whole.

The figures Mr George is referring to come from the industry regulator, the Gambling Commission. At first glance, they do look statistically stable, with 0.6% problem gamblers in 1999 and either 0.6%, 0.7% or 0.8% in 2015.

But there are considerable reasons to believe that these figures are not comparable.

The Gambling Commission says the questions asked over the period were pretty similar, but that three different methodologies had been used, so they should not be seen as a continuous trend.

The reason for the uncertainty about the 2015 figure is that it depends what measure of problem gambling you are using.

The 1999 figure is based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) methodology.

The 0.7% figure in 2015 is also from the APA method (although collected differently, which is why it is not comparable) while the 0.6% is based on the Problem Gambling Severity Index. The 0.8% is people who show up as problem gamblers by either method.

Under the circumstances and given the Gambling Commission's caveats, it is reasonable to conclude that we do not know whether problem gambling is more or less of a problem than it was 15 years ago.

While it is difficult to compare over such a long time, it is possible to compare problem gambling across types.

The latest report from NatCen says the lowest levels of problem gambling were found among those who took part in the National Lottery - 1.3% of them were problem gamblers.

The top five activities with the highest proportions of problem gamblers were:

- Spread betting 20.1%

- Betting exchanges 16.2%

- Playing poker in pubs or clubs 15.9%

- Betting on events with a bookmaker (not online) 15.5%

- Playing machines in bookmakers 11.5%.

Another claim came from Labour deputy leader Tom Watson who said figures show that gambling addiction costs the economy £1.2bn a year.

The figure actually comes from the IPPR think tank and is the top end of a huge range. 'People who are problem gamblers are associated with between £260m and £1.2bn a year of extra cost to government,' the report says.

Such a big range would already be setting off alarm bells if the report did not warn: 'Due to limitations in the available data, these findings should not be taken as the excess fiscal cost caused by problem gambling.'

Printable Addiction Severity Index

There is plenty of interesting analysis of the costs created by problem gambling including things like crime and extra benefits, but it is not reasonable to use this as an excess cost to the government and certainly not only to use the top of the range.